At FORCE and in our Monument Quilt project, we think about healing as being lifelong and non linear. For some of us, activism is part of our healing journey. For you, does activism, advocacy, and/or telling your story connect with what healing looks like – if so how? If not, can you talk about what is important in your healing process as a survivor?

My healing process has been non-linear. Healing occurred in different stages, and in varying degrees. It was God’s way of being patient with me – allowing me to speak and advocate. This is extremely important because, for years, I experienced trauma; and, I didn’t come to grips with it until it gripped me. Layers of trauma had to be delicately pulled back as I sat in the truth of my experience. I had to forgive, be accountable, and ultimately love who I am – not who society wanted me to be. I enjoy physical activity as a form of healing and I am always supportive of each person’s journey. I always remind myself to look within – check on me, first. So, I’m not pouring-out from an empty cup.

This work is difficult on the mind, body and soul. Can you talk about what sustains you, and what brings you joy, so that you can continue on?

Any form of advocating for humanity and human suffering is taxing on a person’s whole being. What sustains me is acknowledging what I feel. Sometimes, I don’t have words for it; and sometimes I do but, I’m in denial. Either way. I try to be honest with myself. This is an act of surrender – everyday, several times a day. I am willing to do this because I have to love me the same way I love my family and dearest friend. It requires owning, and loving, every single part of myself – good, bad, and indifferent. Being true to myself brings me joy. I’m not perpetrating in spaces and, having to “fake being fine”; and I encourage others to do the same. When people hear this, I see the look of relief on their faces. They exhale. And that, makes me happy. We know it’s OK.

Black women have always been in the forefront of the movement to end sexual and domestic violence with an uncompromising focus on how the assault and aftermath always interlocks with racism. Can you talk about this legacy and how you see yourself building on it?

I would say, if we look back at previous movements that promoted social justice, equality, and human rights, black women have always shown the courage to be front and center, and the strength to stand in the gap and tow the line. This is one of the remarkable attributes of black women that make me most proud to be a black woman. The best way for me to build on this legacy is to walk in my own truth – the way God has purposed me to do. This requires some deep self-reflection and the ability to accept accountability. Through this work, and growth, we hope to take back the power that was given away, or taken away.

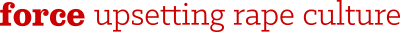

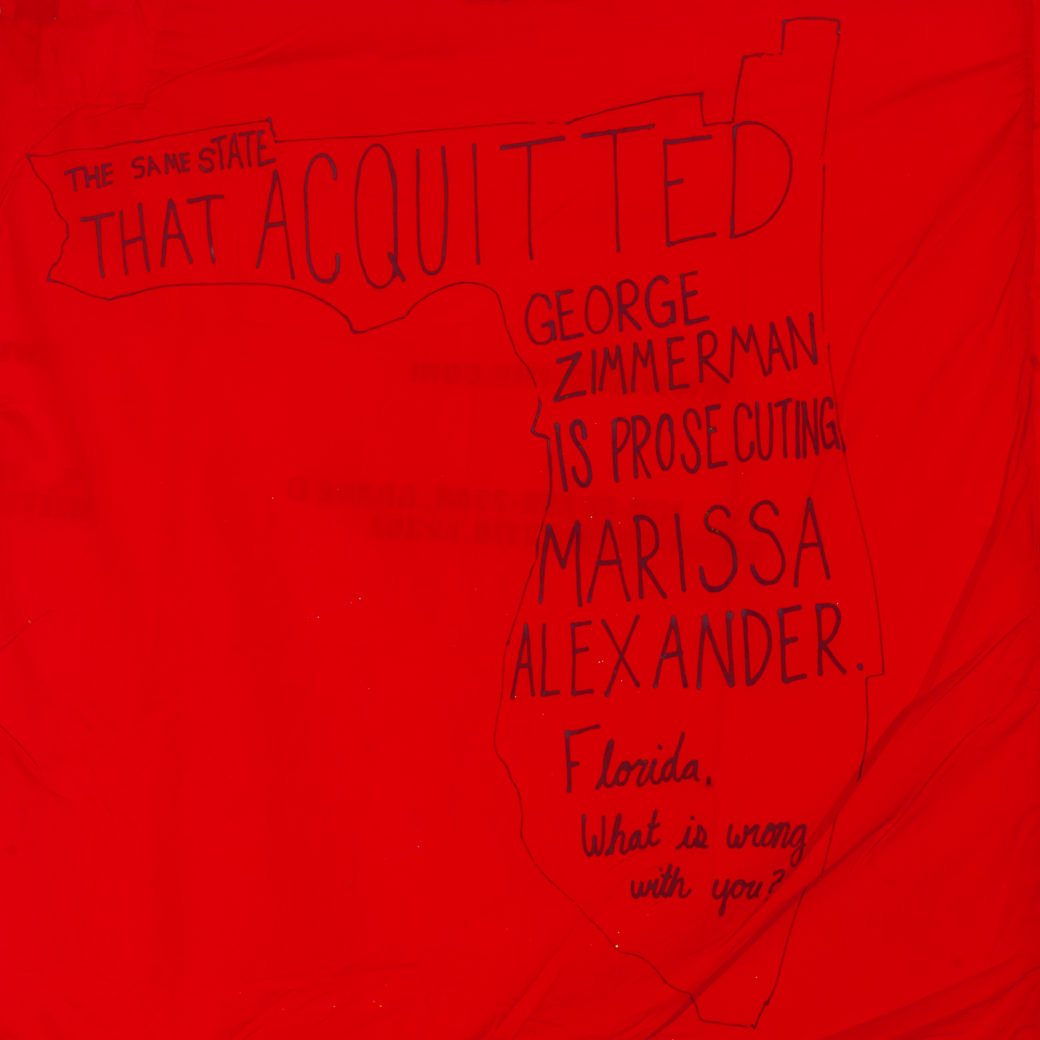

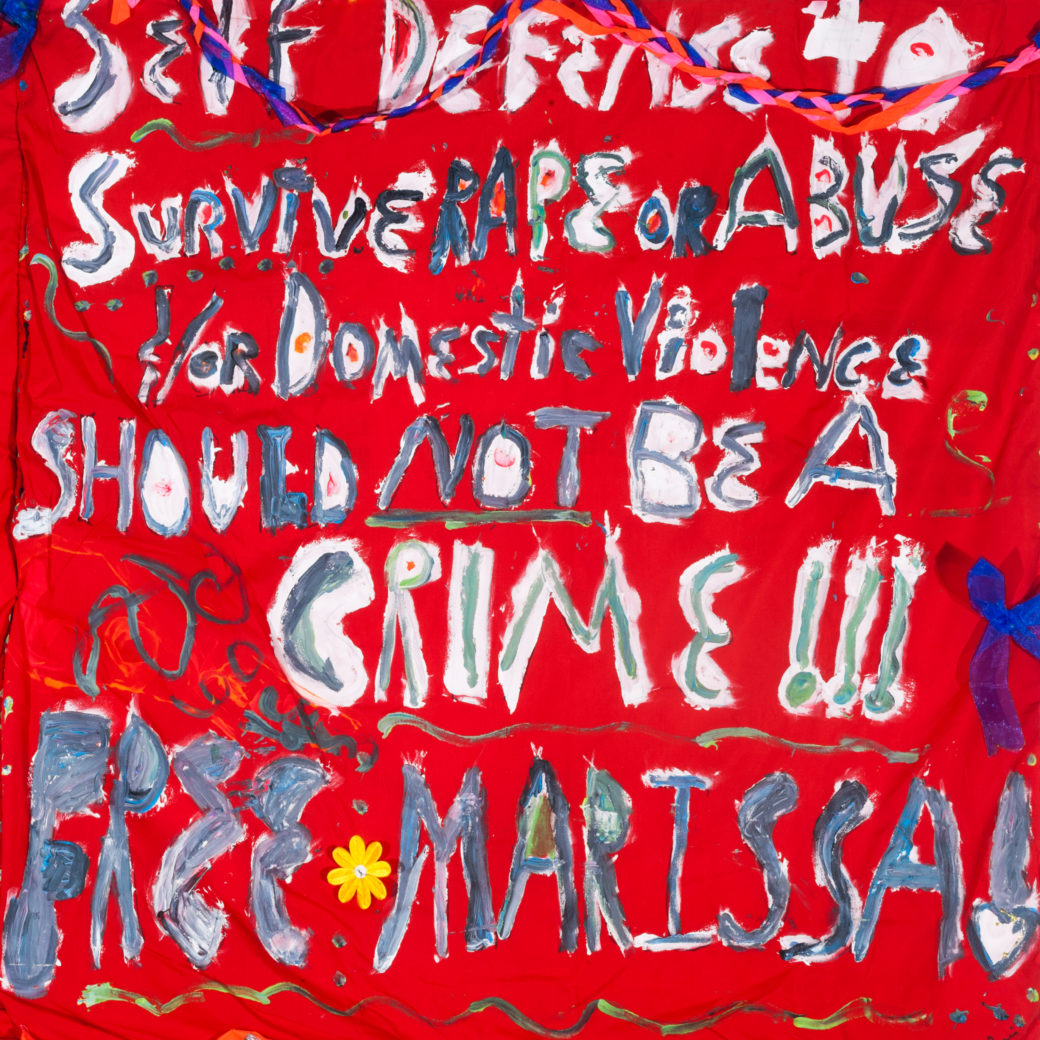

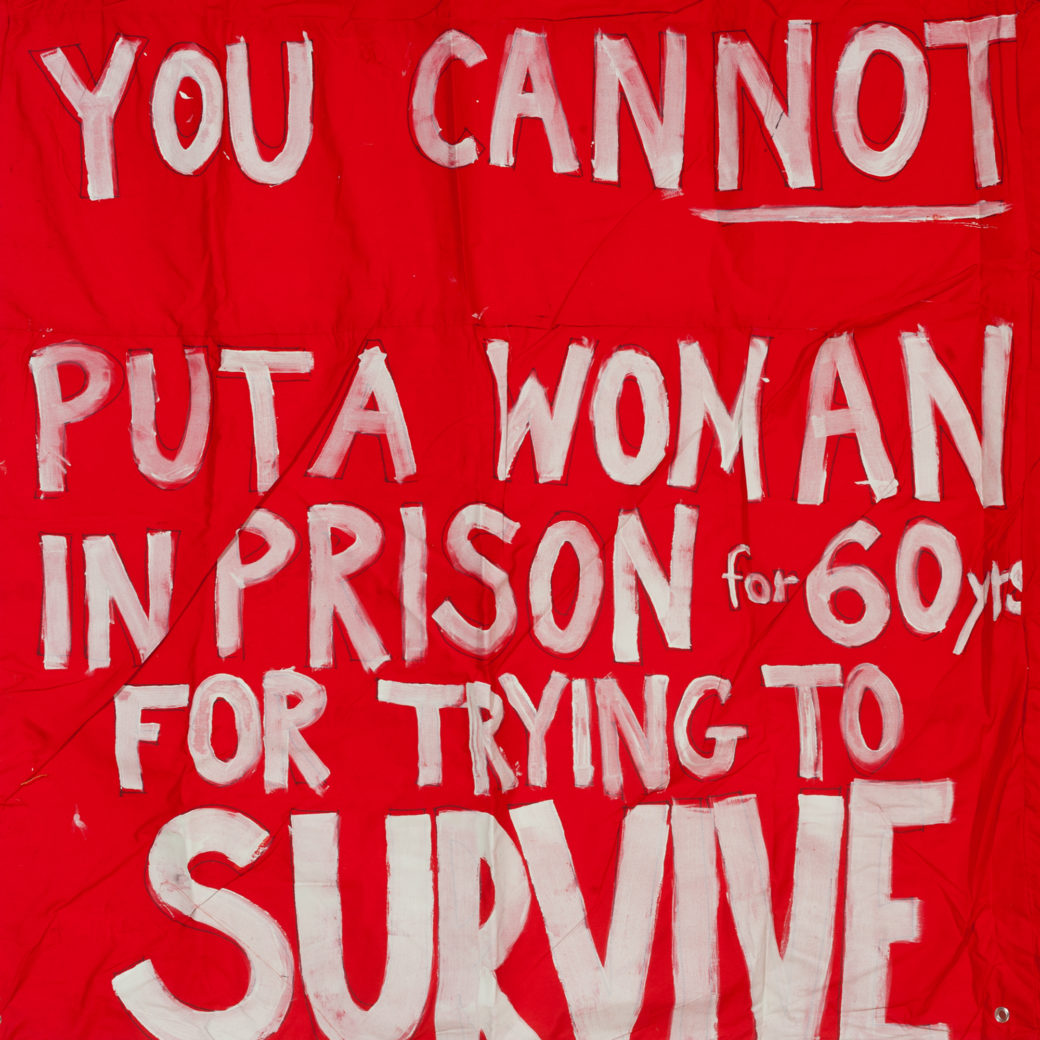

We were honored to collect quilts to bring more visibility to your case and show your the number of survivors who support you, and are so grateful that you can come and speak at the culminating display of the Monument Quilt project. Can you talk about what it means to you for communities of survivors of sexual or intimate partner violence to organize together and in solidarity with one another?

It’s an honor for advocates, activists, and survivors to stand in solidarity and organize in such a creative way. I was traumatized for almost 8 years. For half of that time, I had to live my life under a microscope – with school-aged children, including a 3-year old with whom I was attempting to establish a relationship. That was particularly difficult because I had been out of her life for 3 years.